Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

This article may contain affiliate links. If you click on these links and make a purchase, we may earn a commission at no extra cost to you. We only recommend products and services we trust and believe will add value to our readers. Thank you for supporting Yesteeyear!

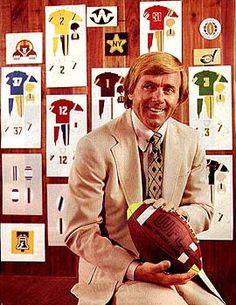

The World Football League was born with swagger, ambition, and the kind of bold vision that made football fans sit up and pay attention. When the league launched with 12 teams in July 1974, its founder, Gary Davidson, confidently predicted a globe‑spanning operation, imagining franchises not only in American cities but also as far away as Honolulu, Madrid, Mexico City, Toronto, and Tokyo. A fast‑talking sports entrepreneur, who had already rattled the establishment through his work with the ABA and WHA, Davidson set out to shake up pro football next — and he wasn’t shy about saying so.

But if the World Football League dreamed big, it stumbled even bigger. Within just five months, two teams folded, three relocated, and Davidson himself was pushed out. Financial freefall soon followed: the league hemorrhaged $20 million in 1974 and another $10 million in 1975 before collapsing midway through its second season. One former commissioner, Chris Hemmeter, summed up the league’s fate bluntly, calling it “the biggest disaster in professional sports history.”

And yet — for many who played in it — the WFL was unforgettable in all the right ways. Stripped of NFL‑level salaries, stable ownership, and even basic necessities like dependable equipment or functioning practice facilities, players discovered a purer form of the sport. Former Buffalo Bills lineman Mike McBath captured the unlikely magic best: “Had the most fun of my life… Didn’t make any money, but… there are still people in this world who would play the game only for the love of it.”

That contrast — soaring ambition vs. constant chaos, financial ruin vs. raw joy — is what makes the WFL one of the most fascinating, chaotic, and strangely endearing chapters in pro football history. This article dives into that wild ride: the grand plans, the rapid unraveling, the unforgettable characters, and the enduring stories from the league that tried to change football… and somehow succeeded, even in failure.

The World Football League wasn’t conceived as just another upstart—it was designed as a full‑scale challenger to the National Football League, driven by the bold ambition of its founder, Gary Davidson. A lawyer and sports entrepreneur with a history of launching rival leagues, Davidson had already helped create the American Basketball Association (ABA) and the World Hockey Association (WHA) before turning his attention to football. By 1973, he was openly declaring that the NFL had “become arrogant and fat,” calling for a new competitor that would force change in professional football.

From the beginning, the WFL’s aspirations were enormous. When the league formally launched with 12 teams in July 1974, Davidson proclaimed that it would grow into a truly worldwide operation. He envisioned a bold global footprint unmatched in pro football history at the time.

The World Football League aimed to distinguish itself immediately. The league planned a 20‑game regular season, six more than the NFL played, and scheduled most contests on weeknights, hoping to avoid head‑to‑head competition with the established league. This aggressive scheduling was part of a larger strategy to present an accessible, fast‑paced alternative product. But the league’s rush to launch in 1974—accelerating its originally intended 1975 start—left many franchises scrambling for staff, finances, and infrastructure long before the opening kickoff.

Yet in the WFL’s earliest moments, the optimism was unmistakable. On the field, attendance looked strong; off the field, the WFL made headlines by signing star NFL talent to future contracts, signaling it was serious about competing for market share and fan attention. But the league that had promised to “take on the big boys” was already laying the groundwork for deeper instability. Many ownership groups were under‑capitalized from the beginning, and several teams lacked resources for even the most basic operations. Franchises began to relocate before playing a single down, and behind the scenes, the league’s financial reality was far shakier than its ambitious PR campaign suggested.

Still, in those early months, the WFL represented something fresh: a challenger with swagger, imagination, and a founder who believed the time had come to reshape professional football. It was a league born from the conviction that the NFL could—and should—be pushed. And for a brief moment, fueled by audacity and global dreams, it seemed as if Gary Davidson’s renegade vision just might pull it off.

When the World Football League kicked off its inaugural season in 1974, it did so with an impressively broad footprint: 12 franchises, spread across major U.S. regions and one in Hawaii, each representing a different experiment in the WFL’s bold vision of a nationwide challenger league.

The full slate of 1974 teams included:

These teams formed the backbone of a league attempting to cover nearly every corner of the football‑hungry United States—from Portland to Orlando, Detroit to Honolulu.

The World Football League’s identity was as much about movement as it was about football. There was the instability, from widespread financial struggles and poor stadium arrangements that forced several teams to uproot—some even before their first snap. For example:

The mid-season relocations included a remarkable amount of reshuffling:

This instability shaped the league’s entire identity: a constantly shifting mosaic of cities, uniforms, and ownership groups.

Against all odds, the WFL returned for a second campaign in 1975, but many franchises underwent rebranding or were replaced entirely:

Only two franchises—the Memphis Southmen and the Philadelphia Bell—retained their ownership structures from the previous year, making the 1975 WFL feel like “a nearly completely different entity.”

The WFL stretched across:

This national reach was ambitious, but as financial cracks spread, so did team mobility. Cities like Charlotte, San Antonio, and Shreveport became unexpected last‑minute hosts for displaced franchises.

What emerges from both files is a portrait of a league whose very geography reflected its spirit: bold, creative, chaotic, and constantly on the move. The WFL’s team map shifted so often that fans struggled to keep up—but this instability also contributed to the league’s unique, almost mythic charm.

Even with teams folding, relocating, and rebranding at a dizzying pace, the WFL managed to deliver competitive football, passionate fanbases, and a fascinating—if turbulent—snapshot of what an audacious challenger league looks like.

From the very beginning, the World Football League made one thing clear: it intended not only to compete with the NFL, but to steal its stars. This aggressive approach became one of the WFL’s defining features—and one of its most destabilizing.

One of the most dramatic talent raids in football history occurred when three marquee Miami Dolphins legends—Larry Csonka, Jim Kiick, and Paul Warfield—signed with the WFL’s Toronto Northmen, who later relocated and became the Memphis Southmen. Their combined deal was worth an astonishing $3.5 million, a record‑shattering sum for the era.

The significance of this cannot be overstated: these were Super Bowl champions at the height of their fame. Their signing proved the WFL could pull megastars directly from the NFL’s elite.

The NFL’s quarterback ranks were shaken by several high‑profile defections:

The possibility of losing both of their top quarterbacks at once sent the Raiders—and the rest of the NFL—into panic.

One of the WFL’s biggest innovations (and headaches for the NFL) was its liberal use of future contracts—agreements that allowed NFL players to sign with the WFL today and join the league once their current NFL deal expired. Dozens of such signings took place, including:

The WFL claimed by June 1974 to have roughly 60 NFL players under contract, many of whom were waiting to defect the moment their obligations ended.

The WFL’s signings had consequences that extended far beyond its own short lifespan:

The WFL’s recruitment spanned every position group. Some examples include:

Some jumped as investors or coaches, too:

Not all WFL signings stuck. Courts intervened in several cases, such as with L.C. Greenwood, Craig Morton, and Ken Stabler, who all had WFL contracts voided or blocked, forcing them to remain in the NFL.

Even though the WFL folded after just two seasons, its talent raids had long‑lasting effects:

The WFL may have been unstable, chaotic, and short‑lived, but for a brief moment, it reshaped the balance of power in professional football—not by outplaying the NFL, but by out‑recruiting it.

One of the most distinctive legacies of the World Football League was its rulebook. Unlike its financial structure, the WFL’s on‑field innovation was bold, coherent, and surprisingly influential. Many of its experimental rules were either later adopted by the NFL or became enduring features of other football leagues.

The WFL did not follow the traditional football scoring model. Instead:

This tweak removed the automatic extra‑point kick and introduced strategy and uncertainty to every post‑touchdown sequence. While the NFL didn’t adopt the Action Point directly, later leagues (including the XFL and CFL) would embrace similar concepts.

To create a more open and continuous kicking game, the WFL eliminated the fair catch on punts. As well as, requiring covering players to give the returner a five‑yard halo—similar to Canadian football’s “no yards” rule.

This approach encouraged returns and kept plays dynamic. While the NFL retained the fair‑catch rule, the idea of incentivizing returns influenced later experimental leagues.

The WFL allowed an offensive back to move toward the line of scrimmage at the snap, provided he remained behind the line at the moment of the snap.

This rule was taken directly from Canadian football and previewed later adaptations in indoor and arena leagues.

The WFL didn’t stop at gameplay—it changed the equipment too. The league used:

While the NFL never adopted this idea, alternate football designs would surface in leagues like the USFL and XFL decades later.

Even though not all WFL rules were embraced widely, they significantly broadened the sport’s tactical vocabulary. The WFL’s innovations helped:

Some WFL rules eventually spread to the CFL and other leagues, a sign that the WFL’s most daring ideas lived on even after the league itself collapsed.

If the WFL’s rulebook was bold and inventive, its financial and operational reality was the opposite: unstable, improvised, and often outright surreal. Many stories paint a vivid, chaotic picture of a league unraveling in real time—where unpaid bills, collapsing franchises, and frantic last‑minute relocations became the norm rather than the exception.

From its very first season, the WFL’s finances were in shambles. As early as 1974, the league was losing money at a catastrophic scale:

Some cities briefly saw good crowds, but both Philadelphia and Jacksonville were later exposed for inflating attendance by giving away massive numbers of free tickets.

Among the most infamous financial disasters was the Detroit Wheels, whose 33 owners chipped in out‑of‑pocket like a recreational club team:

Eventually, the league stepped in and took over the franchise, but the Wheels folded shortly after.

There are many stories that illustrate just how unstable the WFL became:

These events weren’t the exception; they were the WFL experience.

By October 29, 1974, founder Gary Davidson resigned as commissioner amid mounting chaos. He was replaced by Donald J. Regan on an interim basis, but by then the league was already in freefall.

By 1975, there were only three teams, the Memphis Southmen, Philadelphia Bell, and The Hawaiians, that were able meet payroll consistently. Attendance plummeted even further and multiple franchises shut down or were replaced.

The league officially folded on October 22, 1975, unable to maintain even the basic financial requirements for operation.

In the end, the WFL became defined not by its football innovations or star players, but by its chaotic collapse—a league where unpaid salaries, last‑minute relocations, bankruptcy, and bizarre administrative decisions drowned out even the most dramatic on‑field moments.

Yet, as many players reflected, it was also one of the most memorable adventures of their careers—chaos and all.

The culmination of the WFL’s inaugural 1974 season was as chaotic, dramatic, and surreal as the league itself. World Bowl I—the first and only championship game in WFL history—became a perfect microcosm of everything the league embodied: ambition, instability, financial collapse, and unforgettable on‑field drama.

Scheduled for December 5, 1974, World Bowl I was held at Legion Field in Birmingham, Alabama. The matchup pitted the Birmingham Americans against the Florida Blazers. But even reaching kickoff was a miracle:

Financial desperation also shaped the playoff picture with the Charlotte Hornets, who had earned the right to host a playoff game, withdrew from the postseason due to poor ticket sales, forcing the Philadelphia Bell into their place.

The game began surprisingly smoothly given the backdrop of financial chaos. Birmingham’s offense controlled the early quarters:

The game looked over—but the WFL, true to form, had chaos left in store.

Led by quarterback Bob Davis and running back Tommy Reamon, the Florida Blazers mounted a furious fourth‑quarter rally:

But the Blazers never got the ball back. Birmingham drained the final minutes, sealing victory and the only World Bowl title ever awarded.

As the game ended, disorder took over—again, in classic WFL fashion:

And then came the most iconic moment in WFL history:

Sports Illustrated would later call World Bowl I:

“The first, and possibly only World Bowl.”

A prophecy that proved true.

In the immediate aftermath:

Though the WFL limped into a second season, it would never again stage a championship. As the league folded in October 1975, cementing World Bowl I as its lone title game.

Though the World Football League burned fast and collapsed spectacularly, its influence radiated far beyond its two turbulent seasons. The WFL’s innovations, talent raids, media presence, and competitive pressure reshaped the landscape of professional football across the U.S. and Canada. Far from being a forgotten footnote, the WFL left fingerprints on rules, player mobility, coaching careers, and even the NFL’s rise to national dominance.

The WFL’s aggressive signing of NFL superstars, including those members of the Miami Dolphins, dramatically altered player leverage:

The league’s signing spree exposed how undervalued many NFL players were—ultimately pressuring the NFL to modernize its labor practices.

The WFL introduced rule changes that influenced football for decades:

These innovations helped establish the WFL as a rule‑changing laboratory whose ideas were often ahead of their time.

Numerous WFL alumni became influential NFL leaders, such as Marty Schottenheimer, Jack Pardee, and other early WFL coaches and personnel later built successful NFL careers.

The WFL helped launch or strengthen the careers of figures who would shape professional football strategy and culture for decades.

Despite its financial turmoil, the WFL generated extensive media coverage and public interest. The league contributed to the overall rise in football popularity in both the United States and Canada. This surge helped push the NFL into its eventual position as the most watched and culturally dominant sport in the U.S.—surpassing even baseball.

In short, the WFL expanded the football audience, even as it failed to sustain itself.

The WFL lasted barely two seasons, but the ripple effects in labor, rules, coaching, and fan culture endured long after the repossessed jerseys, bounced checks, and relocated franchises faded from view.

“The World Football League’s attempt to gain a following… left a lasting imprint on professional football in general.”

The WFL may have failed as a business—but it succeeded as a catalyst, pushing football forward in ways still visible today.

For all its instability, the World Football League was fueled by enormous ambition. The WFL did not see itself as a minor‑league alternative—it saw itself as a future global juggernaut. Many of its most daring aspirations never materialized, but together they paint a fascinating picture of what the WFL hoped to become before collapsing under its own weight.

From the league’s earliest days, founder Gary Davidson envisioned a worldwide footprint far beyond the NFL’s reach:

This global vision remains one of the most striking “what‑ifs” in football history—a bold expansion strategy decades before the NFL set foot in Europe.

The WFL sought to radically reshape professional football scheduling:

The WFL saw itself as a legitimate competitor to the NFL, Davidson and fellow founders believed the WFL could potentially rival the long‑established NFL, not simply coexist with it.

The talent raids—signing stars like Larry Csonka, Jim Kiick, and Paul Warfield—were meant to accelerate that trajectory, but the league could never stabilize long enough to capitalize on its shockwaves.

One of the most forward‑thinking unrealized ideas was the WFL’s proposed overhaul of player acquisition:

This system was intended to counter the NFL’s dominance and create a path for the WFL to rapidly stock its teams with recognizable talent. The idea never came to fruition because the league did not survive long enough to fully test it.

Despite the catastrophe of 1974, the WFL mounted a surprisingly structured return in 1975. They offered new branding, reorganized ownership, and revised scheduling that were intended to provide stability. Yet even with these changes, the league folded on October 22, 1975, before it could see whether its reforms might finally achieve financial and competitive footing.

Had the league made it through the full season, its expansion plans—including potential new markets and more polished media arrangements—might have reshaped its legacy.

The WFL died under enormous debt, mismanagement, and logistical chaos—but its dreams were bigger than its budget.

“Davidson intended for the WFL to spread American‑style football across the world.”

If even a fraction of that vision had materialized, the football landscape today might look entirely different—more global, more competitive, and more innovative.

The World Football League began with an audacious dream: a bold, global challenger that would “take on the big boys” of the NFL, as envisioned by founder Gary Davidson. In 1974, with twelve franchises and plans for teams stretching from Honolulu to Tokyo, the league appeared ready to disrupt professional football forever.

But the WFL’s spectacular ambitions quickly collided with financial instability, operational chaos, and a rushed inaugural season. Teams relocated mid‑year, players went unpaid, and franchises folded on the fly. The Detroit Wheels became the symbol of this collapse—unable to pay travel costs, lacking uniforms, and eventually fleeing the city under cover of night before folding entirely.

Even amid disarray, the league produced moments of genuine football drama and cultural resonance. World Bowl I, the WFL’s only championship, encapsulated it all: unpaid teams, a dramatic 22–21 finish, and the surreal sight of sheriff’s deputies repossessing the Birmingham Americans’ uniforms immediately after the game.

And yet—despite its failure—the WFL’s impact echoed far beyond 1975.

The league forced the NFL to reckon with stagnating salaries and rigid player‑movement systems after WFL signings lured away stars like Larry Csonka, Jim Kiick, and Paul Warfield. The resulting talent void in Miami cleared the path for rising dynasties such as the Pittsburgh Steelers and Oakland Raiders.

WFL rule innovations—including changes to overtime structure and gameplay mechanics—influenced leagues that followed and, eventually, elements of NFL rule modernization.

The WFL also became an unlikely talent incubator. Coaches such as Jack Pardee and Marty Schottenheimer built foundational career experience in the league before making significant marks in the NFL.

Perhaps most importantly, the WFL helped elevate football’s overall popularity. Media coverage and fan engagement surrounding the WFL contributed to the sport’s broader rise in the United States and Canada—helping the NFL become the country’s most popular sport.

In the end, the WFL stands as a paradoxical achievement: a league that failed spectacularly yet changed football meaningfully. Its collapse was swift and chaotic, but its influence—on players, coaches, rules, and fan culture—has endured for decades.

The WFL may not have survived long enough to achieve its global aspirations, but its boldness reshaped the sport and left a legacy far larger than its brief two‑season lifespan.